As a kid, I thought that the greatest thing you could ever grow up to be was an astronaut. I know it sounds cliché, but when I was in grade school, I thought that there was no greater calling. Much of my love for science fiction stems from the science of space exploration.

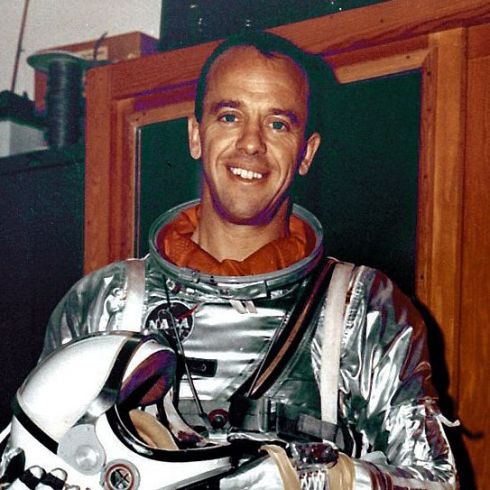

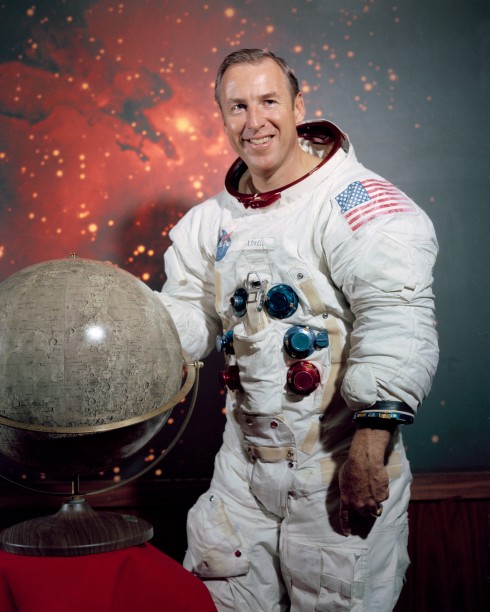

There was just something about the mystique of braving the extreme dangers of outer space and coming back safely that was the ultimate in cool. Names like Aldrin, Shepard, Lovell, and even their Soviet cosmonaut counterpart, Yuri Gagarin, were the giants of my world. Let’s talk a little about why.

The Right Stuff

I believe now, as I did back then, that astronauts and what they do represent the best of us. Astronauts themselves embody peak intelligence, physical and mental discipline, courage, commitment and a willingness to push the limits of what we think is possible. On the odd chance that any astronaut, past or present, should read this blog, you are the stars of my sky. Truly. The same goes for the multitude of scientists, engineers and technical specialists that help make it all happen.

The space program, on the other hand, is the culmination of our greatest scientific, technological, and engineering efforts in an ongoing attempt to satisfy our curiosity about the universe around us — a curiosity that can never truly be satisfied. In essence, it’s our best people, doing the best work, for the greatest reason. It’s the noblest part of our humanity writ large. Yeah, I know I may be laying it on a little thick, but I really believe that.

Two Space Centers

While I’ve lived in Texas my whole life, the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston was just far enough from where I went to school that we never went there as part of any field trips. This is the place that James Lovell was addressing when he said “Houston, we’ve had a problem here” during the Apollo 13 mission. It was only as an adult that I got to sit in the viewing room, among the original red velveteen seats overlooking Mission Control where Lovell’s message was received. I’ve been there a few times now, and I can’t help but be inspired every time I go. Houston is not exactly in my back yard, but it’s a weekend trip, like going down there to go to Texas Renaissance Festival (yes, the one from the documentary), or any of the many excellent museums there.

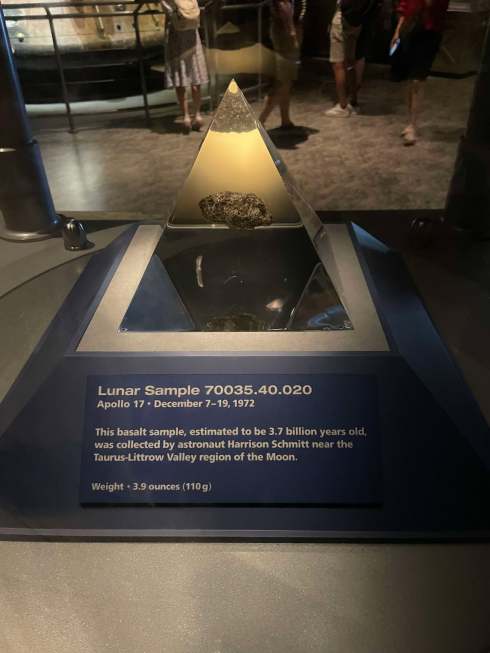

The part of NASA that I had never visited until recently, however, is the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Cape Canaveral, Florida, where the Mercury and Apollo missions, just to name a few, launched from originally. Rockets still launch from there today, though now commercial rockets from Blue Origin, Space X, and others are in the lineup as well.

For me, this was the place where the rubber met the proverbial road of the space program. This was the stage where it all happened, both the towering accomplishments of Apollo 11 and the tragedy of Apollo 1. Following through on President Kennedy’s aspirations to put a man on the moon is nothing less than a triumph of the human spirit.

Perhaps the most tangible symbol of this is the Saturn V rocket, which was key to the moon missions. If you’ve never seen one before, it’s massive. As tall as a 30-story building, taller than the Statue of Liberty, when you look at this rocket, you start to get an idea of what it took to get to the moon. The difference between the gigantic superstructure of the Saturn and the almost ridiculously small command module at the very top is unbelievable. It’s humbling to stand in the shadow of this titan and begin to understand the number of scientists, engineers, construction specialists, and other personnel it took to design and build something like that.

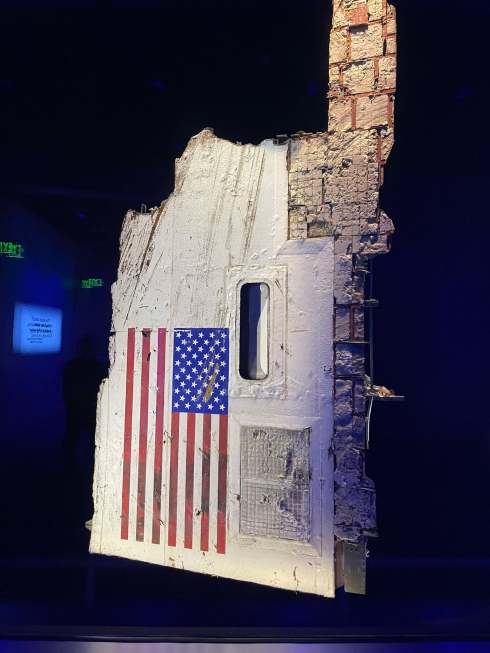

Now, I’m not blind to the driving forces behind the early space program and the finer points of the Space Race, but when I look up at a Saturn V, I see only humanity at its finest. It’s the same kind of feeling when I see a space shuttle. Well, the KSC has the Space Shuttle Atlantis (OV-104) on the grounds as well, and seeing it up close was a powerful experience.

It’s strange; the shuttle is both bigger and smaller than I had guessed. Still, I could only just stand there, looking at her for a long while. You can still see the pits and scars on the black tiles of her aft section, near her thrusters, made from micro-meteors. Even writing about it gives me chills.

Much like my trip to Graceland, I think I’ve been on a journey to the KSC for a very long time, long before I knew exactly why or could even find it on a map. I think my trips to the JSC and, ultimately, the KSC were inevitable, and I can’t wait to go back one day.

The Next Generation

Of course, there are any number of interactive experiences and displays scattered around the KSC, even a couple of rides you can go on that simulate space exploration. Much like the JSC in Houston, I definitely get the impression that many of the attractions are meant for school field trips and families with children.

I’m glad of that. Younger generations deserve to have an exciting and inspirational vision of the space sciences, astrophysics, and exploration the same as me. I mean, I grew up eating astronaut ice cream and drinking Tang, and I’ve never doubted for a minute just how important the space program is to all of us. Not just those of us in the United States, but all of us.

Why It’s Important

I’ve heard the arguments against it all, of course. I even understand where these arguments come from. Normally they go something like this: How can we afford to spend all that time, effort and money on space stuff when we have so many problems down here at home?

For me, that’s the wrong question, which boils down to: How can we afford not to? We can talk about the tangible things that are directly attributable to the space program like the aforementioned Tang, non-stick coating for pots and pans, and so on, but many of the advances we enjoy today, like computers, cell phones, the internet, have their roots in the pursuit of space.

But more than that, consider this: The space program is a catalyst for science and technology that isn’t war. It is a peaceful way for us to learn more about life, the universe, and everything. Space is also one of the few fronts where nations that are actively hostile on the ground can still cooperate up there.

Final Thoughts

Space is the one place where humanity can really come together for the betterment of all. At least, that’s how it’s been, and I hope it continues on that way. I know that sounds a bit pie-in-the sky, and maybe it is, but that is one of the reasons that the space program resonates so heavily with me. It’s the best of us, exploring the unknown, and uniting in a shared purpose.

And what could be more human than that?

Thanks for reading.